"What do you need that wig for?

...Are you going to wear it?"

"No! It's for my head."

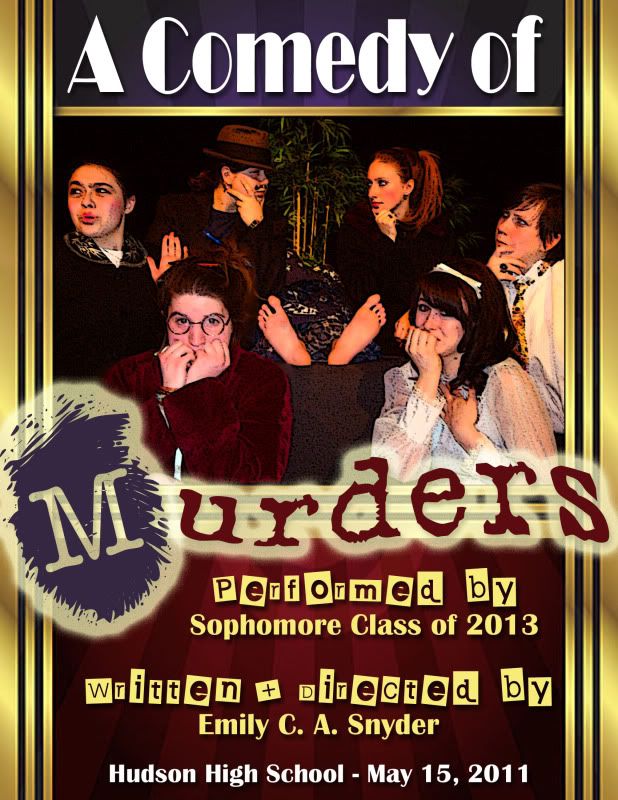

Yet another one for the annals of why I love theatre and why it's so weird and yet so all-inclusive. So, far from making fake decapitated heads (as in the above exchange), I'm currently looking up and into the nature of the Ghost in Hamlet. Or rather, I'm more particularly interested in the Ghost as a religious division line. Now, at least according to Hamlet in Purgatory, most Protestants - or at least Puritans - at that time believed that anything ghostly was either demonic or angelic in origin. Catholics - again according to this book, which I only mehishly recommend (see the review "Better on Purgatory than on Hamlet" to approximate why the meh rating) - tended to view ghosts either as demonic, angelic, or as souls from Purgatory.

Now, for myself, I've been asked regularly every year by the Freshmen (dunno why it's always the Freshmen, never the upperclassmen, but therey'are) "What about ghosts?!!?" My response has been something nebulous, but basically: "When we think about ghosts coming and haunting places, or Caspar or any of those things - well, I personally have a tough time holding with it - or with ideas that souls are trapped here on earth in such a manner. However, I don't know everything. But as far as I understand, I'd suppose that what we term ghosts are usually either demons, or angels, or sometimes souls sent back for a purpose and therefore for a short time - to pass on a message, etc." My practical side would, honestly, like to laugh at the idea of ghosts at all - except that my practical side has also seen something that I simply couldn't explain, and worse, that practical side was held up by a second person also seeing the exact same thing I saw.

Story time: when in Europe for a semester, a group of us were coming back from a trip on a very crowded train. We were looking for a compartment that could seat all of us together - preferably an emtpy compartment. (There were six of us, the compartment could seat eight.) My friend, who is now a priest!!!, Nick and I went forward to scout out availability and we both spotted one compartment that only had one old gentlemen in it. Since he looked not only harmless but even a little ducky and since there were seven remaining seats in the compartment, Nick and I decided to open the door and ask the gentlemen if our party could join him. We opened the door, and could clearly see his face - he was looking rather quietly and peacefully at the opposite wall, he wore an Austrian hat and a neat tailored suit that wasn't quite Austrian but gave that same sort of impression. I want to say he leaned his arms on a cane, but I can't recall. The important thing is that we could clearly see his whole body.

Nick stepped into the compartment, and then a moment later, I swung my foot over the threshhold. As soon as I did so - the man disappeared.

Immediately, we heard our friends racing up the corridor calling out for us. We called them towards us, and then turned to each other and said, "Did you see?" "Yes." "All of him?" "Yes." "And then he just...?" "Yes." We didn't mention it to our friends at the time, but piled into the compartment. Later, both Nick and I went over what the man looked like, and agreed on every particular we brought up. And so, although I should like to scoff at the notion of such things, my waking brain simply can't.

So what, if anything, do Catholics teach? Mark Shea, a leading modern apologist, indicates that unsurprisingly there IS no Catholic doctrine on the matter other than Hamlet's own reponse to Horatio's "'Tis strange" "And as a stranger, therefore, give it welcome. There are more things between Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in [y]our philosophy."

So what does Shakespeare and Hamlet respectively believe about the Ghost? It seems fairly clear that the one followed soon after by the other admit to the third Purgatorial possibility. In such an age where religion was the politics, and where it was literally worth a person's own immortal soul to speak about the state of others, Shakespeare makes the Ghost the essential and inextricable catalyst of Hamlet. Moreover, although Horatio (who I think it's fair to play as Hamlet's soul) expresses doubt, and Hamlet himself when once alone with the Ghost is cautious, they are swayed when once the Ghost declares that:

Immediately after, Hamlet - who is late from Whittenberg, a Lutheran divinity school - begins swearing by St. Patrick, the patron saint of souls in Purgatory - as well as a possible dig against anti-Irish sentiment - and using Church Latin "Hic et ubique?" - which is expresses only only solidarity with Rome and traditional Christendom but which also expresses the dogmatic belief about the nature of God being "here and everywhere." Hamlet's journey towards his Catholic roots follows the course of the whole play, and is consistently spurred on by the Ghost's presence. Hamlet, wisely, still distrusts his own discernment about the Ghost and the Ghost's word and so tests his uncle's guilt first. But once so tested (and that part digresses into the nature and use of plays and Shakespeare's own seditious use of the theatre), Hamlet again delays his revenge when he finds Claudius praying.

Now the dual soliloquy scene I find interesting. (Perhaps even more interesting since we blocked it last night. The repetition of the word "there" still makes me giggle and roll my eyes. Sigh. But fond sigh.) First, we must ask whether Shakespeare is looking at Denmark as an essentially Catholic or Lutheran state. On the one hand, the original story of Hamlet from the Gesta Danorum is from the height of Medieval Christendom, and was indeed written under the patronage of a Bishop. However, the legend of Prince Amleth appears to predate the introduction of Christianity to Denmark. Which distinction may have made no difference to Saxo Grammaticus (the author of the Gesta Danorum), since the Christianization of ancient pagan legends and histories was common among north countries. Moreover, it would have made no nevermind to Shakespeare either, since he regularly mixes his mythologies as seem to suit his poetry.

But all this speculation about the original story might be fruitless since it appears that Shakespeare is actually doing a rewrite not of Saxo Grammaticus, but rather of a fellow playwrite who'd written what scholars call the Ur-Hamlet. So, although the original text appears to have examined the possibly pagan history through a Catholic lens, Shakespeare himself may have been examining the story via what he knew of his own present day Denmark, which as Lutheran.

And certainly, Claudius does not seek out a priest for confession. Yet, later, during the graveyard scene, a priest (not a pastor nor a divinical much less phycial doctor) is present and speaking about explicitly Catholic burial rites that the priest was apparently strong armed by the King into giving Ophelia despite her "doubtful" death (i.e., her apparent suicide which would not have merited her the Christian burial). So - strike one for Shakespeare's Denmark being Lutheran and another for it being Catholic.

Regardless, during the double soliloquy, Hamlet is willing to concede that Claudius' apparent self-confession (sans priest) may be sufficient to save his uncle's soul from mortal sin. Hamlet shows caution here, but also residual Lutheran theology. Once Hamlet leaves, however, Claudius gives the pithy statement, "My words rise up, my thoughts remain below/Words without thoughts never to Heaven go." That is, his self-confession has no power of absolution. He is unable to feel contrition, and therefore cannot receive grace. (Cf. contrition and absolution here.) Curiously, had Claudius' sought out confession with a priest, he would have been given the penance of having to publically admit his deceptions - something which I doubt Claudius would care to take on. In this scene of fruitless self-confession, Claudius proves himself a sort of Dante's Satan, as he declares, "O limed soul that struggling to be free art more engaged!"

From this point on, Claudius moves towards, if anything, aetheism with occasional whimpering in the face of God. (E.g., when Laertes declares the he would gladly "cut [Hamlet's] throat in the church," Claudius blenches.) Meanwhile, Hamlet moves towards reconciliation with God - in fact, towards reconciliation with a bloody martyrdom (that may have been connected in the minds of Shakespeare's audience with Campion and Southwell):

He immediately goes from this to reconciliation with his "brother" Laertes, (indeed, his potential brother-in-law, thus furthering the metaphor of Cain and Abel). He makes a sort of public Act of Contrition or Confiteor when he declares:

(Indeed, it would be interesting to view the duel at the end of Hamlet as a sort of Mass. It begins with Hamlet's declaration that he will undertake going to - for Elizabethan England - such an illegal sacrament "Let be," progresses to the Confiteor, includes a version of the chalice - here corrupted by the corrupt Claudius - and concludes with the injunction to go in peace and to reenact the story of Hamlet in his remembrance.)

Hamlet, later, realizing that he himself might not be in a state of grace (since he is still planning Claudius' death and since he is in the middle of settling his argument with his brother) refuses the cup from his mother, saying "I dare not yet, by and by." He only receives the cup - drinking the dregs of the poisoned chalice so that Horatio might live - after he has revenged his father and exchanged true reconciliation with Laertes.

Nor is death now a thing to be feared, because Hamlet is reconciled with God. In fact, death is almost to be sought as in the various monks call "Remember thy death!" And Hamlet himself calls for Horatio to tell his story, as we recount to each other the lives of the saints.

Harold Bloom calls the end of Hamlet an apotheosis, and he is quite right to do so. For, far from those tragedies wherein the deaths of the leads are "doubtful" - such as Romeo and Juliet or Macbeth and even to an extent Othello, we are certain sure that Hamlet is going to a place where "flights of angels" might "wing [him] to [his] rest."

Right. Anywho. Must needs block said scene since we're doing it tonight. Enough rambling for today!

Mood: Meh.

Music: Mellow mix a la iTunes

Thoughts: Really, really, really need to clean.

...Are you going to wear it?"

"No! It's for my head."

Yet another one for the annals of why I love theatre and why it's so weird and yet so all-inclusive. So, far from making fake decapitated heads (as in the above exchange), I'm currently looking up and into the nature of the Ghost in Hamlet. Or rather, I'm more particularly interested in the Ghost as a religious division line. Now, at least according to Hamlet in Purgatory, most Protestants - or at least Puritans - at that time believed that anything ghostly was either demonic or angelic in origin. Catholics - again according to this book, which I only mehishly recommend (see the review "Better on Purgatory than on Hamlet" to approximate why the meh rating) - tended to view ghosts either as demonic, angelic, or as souls from Purgatory.

Now, for myself, I've been asked regularly every year by the Freshmen (dunno why it's always the Freshmen, never the upperclassmen, but therey'are) "What about ghosts?!!?" My response has been something nebulous, but basically: "When we think about ghosts coming and haunting places, or Caspar or any of those things - well, I personally have a tough time holding with it - or with ideas that souls are trapped here on earth in such a manner. However, I don't know everything. But as far as I understand, I'd suppose that what we term ghosts are usually either demons, or angels, or sometimes souls sent back for a purpose and therefore for a short time - to pass on a message, etc." My practical side would, honestly, like to laugh at the idea of ghosts at all - except that my practical side has also seen something that I simply couldn't explain, and worse, that practical side was held up by a second person also seeing the exact same thing I saw.

Story time: when in Europe for a semester, a group of us were coming back from a trip on a very crowded train. We were looking for a compartment that could seat all of us together - preferably an emtpy compartment. (There were six of us, the compartment could seat eight.) My friend, who is now a priest!!!, Nick and I went forward to scout out availability and we both spotted one compartment that only had one old gentlemen in it. Since he looked not only harmless but even a little ducky and since there were seven remaining seats in the compartment, Nick and I decided to open the door and ask the gentlemen if our party could join him. We opened the door, and could clearly see his face - he was looking rather quietly and peacefully at the opposite wall, he wore an Austrian hat and a neat tailored suit that wasn't quite Austrian but gave that same sort of impression. I want to say he leaned his arms on a cane, but I can't recall. The important thing is that we could clearly see his whole body.

Nick stepped into the compartment, and then a moment later, I swung my foot over the threshhold. As soon as I did so - the man disappeared.

Immediately, we heard our friends racing up the corridor calling out for us. We called them towards us, and then turned to each other and said, "Did you see?" "Yes." "All of him?" "Yes." "And then he just...?" "Yes." We didn't mention it to our friends at the time, but piled into the compartment. Later, both Nick and I went over what the man looked like, and agreed on every particular we brought up. And so, although I should like to scoff at the notion of such things, my waking brain simply can't.

So what, if anything, do Catholics teach? Mark Shea, a leading modern apologist, indicates that unsurprisingly there IS no Catholic doctrine on the matter other than Hamlet's own reponse to Horatio's "'Tis strange" "And as a stranger, therefore, give it welcome. There are more things between Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in [y]our philosophy."

So what does Shakespeare and Hamlet respectively believe about the Ghost? It seems fairly clear that the one followed soon after by the other admit to the third Purgatorial possibility. In such an age where religion was the politics, and where it was literally worth a person's own immortal soul to speak about the state of others, Shakespeare makes the Ghost the essential and inextricable catalyst of Hamlet. Moreover, although Horatio (who I think it's fair to play as Hamlet's soul) expresses doubt, and Hamlet himself when once alone with the Ghost is cautious, they are swayed when once the Ghost declares that:

I am thy father's spirit,

Doom'd for a certain term to walk the night,

And for the day confined to fast in fires,

Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature

Are burnt and purged away. But that I am forbid

To tell the secrets of my prison-house,

I could a tale unfold whose lightest word

Would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood,

Make thy two eyes, like stars, start from their spheres,

Thy knotted and combined locks to part

And each particular hair to stand on end,

Like quills upon the fretful porpentine:

But this eternal blazon must not be

To ears of flesh and blood. List, list, O, list!

Immediately after, Hamlet - who is late from Whittenberg, a Lutheran divinity school - begins swearing by St. Patrick, the patron saint of souls in Purgatory - as well as a possible dig against anti-Irish sentiment - and using Church Latin "Hic et ubique?" - which is expresses only only solidarity with Rome and traditional Christendom but which also expresses the dogmatic belief about the nature of God being "here and everywhere." Hamlet's journey towards his Catholic roots follows the course of the whole play, and is consistently spurred on by the Ghost's presence. Hamlet, wisely, still distrusts his own discernment about the Ghost and the Ghost's word and so tests his uncle's guilt first. But once so tested (and that part digresses into the nature and use of plays and Shakespeare's own seditious use of the theatre), Hamlet again delays his revenge when he finds Claudius praying.

Now the dual soliloquy scene I find interesting. (Perhaps even more interesting since we blocked it last night. The repetition of the word "there" still makes me giggle and roll my eyes. Sigh. But fond sigh.) First, we must ask whether Shakespeare is looking at Denmark as an essentially Catholic or Lutheran state. On the one hand, the original story of Hamlet from the Gesta Danorum is from the height of Medieval Christendom, and was indeed written under the patronage of a Bishop. However, the legend of Prince Amleth appears to predate the introduction of Christianity to Denmark. Which distinction may have made no difference to Saxo Grammaticus (the author of the Gesta Danorum), since the Christianization of ancient pagan legends and histories was common among north countries. Moreover, it would have made no nevermind to Shakespeare either, since he regularly mixes his mythologies as seem to suit his poetry.

But all this speculation about the original story might be fruitless since it appears that Shakespeare is actually doing a rewrite not of Saxo Grammaticus, but rather of a fellow playwrite who'd written what scholars call the Ur-Hamlet. So, although the original text appears to have examined the possibly pagan history through a Catholic lens, Shakespeare himself may have been examining the story via what he knew of his own present day Denmark, which as Lutheran.

And certainly, Claudius does not seek out a priest for confession. Yet, later, during the graveyard scene, a priest (not a pastor nor a divinical much less phycial doctor) is present and speaking about explicitly Catholic burial rites that the priest was apparently strong armed by the King into giving Ophelia despite her "doubtful" death (i.e., her apparent suicide which would not have merited her the Christian burial). So - strike one for Shakespeare's Denmark being Lutheran and another for it being Catholic.

Regardless, during the double soliloquy, Hamlet is willing to concede that Claudius' apparent self-confession (sans priest) may be sufficient to save his uncle's soul from mortal sin. Hamlet shows caution here, but also residual Lutheran theology. Once Hamlet leaves, however, Claudius gives the pithy statement, "My words rise up, my thoughts remain below/Words without thoughts never to Heaven go." That is, his self-confession has no power of absolution. He is unable to feel contrition, and therefore cannot receive grace. (Cf. contrition and absolution here.) Curiously, had Claudius' sought out confession with a priest, he would have been given the penance of having to publically admit his deceptions - something which I doubt Claudius would care to take on. In this scene of fruitless self-confession, Claudius proves himself a sort of Dante's Satan, as he declares, "O limed soul that struggling to be free art more engaged!"

From this point on, Claudius moves towards, if anything, aetheism with occasional whimpering in the face of God. (E.g., when Laertes declares the he would gladly "cut [Hamlet's] throat in the church," Claudius blenches.) Meanwhile, Hamlet moves towards reconciliation with God - in fact, towards reconciliation with a bloody martyrdom (that may have been connected in the minds of Shakespeare's audience with Campion and Southwell):

Not a whit, we defy augury: there's a special

providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now,

'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be

now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the

readiness is all: since no man has aught of what he

leaves, what is't to leave betimes? Let be.

He immediately goes from this to reconciliation with his "brother" Laertes, (indeed, his potential brother-in-law, thus furthering the metaphor of Cain and Abel). He makes a sort of public Act of Contrition or Confiteor when he declares:

| Hamlet Give me your pardon, sir: I've done you wrong;/But pardon't, as you are a gentleman./This presence knows,/And you must needs have heard, how I am punish'd/With sore distraction. What I have done,/That might your nature, honour and exception/Roughly awake, I here proclaim was madness./Was't Hamlet wrong'd Laertes? Never Hamlet:/If Hamlet from himself be ta'en away,/And when he's not himself does wrong Laertes,/Then Hamlet does it not, Hamlet denies it./Who does it, then? His madness: if't be so,/Hamlet is of the faction that is wrong'd;/His madness is poor Hamlet's enemy./Sir, in this audience,/Let my disclaiming from a purposed evil/Free me so far in your most generous thoughts,/That I have shot mine arrow o'er the house,/And hurt my brother. | Confiteor I confess to Almighty God, to blessed Mary ever Virgin, to blessed Michael the Archangel, to blessed John the Baptist, to the holy Apostles Peter and Paul, and to all the saints, that I have sinned exceedingly in thought, word, and deed, through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault. Therefore, I beseech blessed Mary ever Virgin, blessed Michael the Archangel, blessed John the Baptist, the holy Apostles Peter and Paul, and all the saints, to pray to the Lord our God for me. May Almighty God have mercy on me, forgive me my sins, and bring me to life everlasting. Amen. May the Almighty and merciful Lord grant me pardon, + absolution, and remission of all my sins. Amen. |

(Indeed, it would be interesting to view the duel at the end of Hamlet as a sort of Mass. It begins with Hamlet's declaration that he will undertake going to - for Elizabethan England - such an illegal sacrament "Let be," progresses to the Confiteor, includes a version of the chalice - here corrupted by the corrupt Claudius - and concludes with the injunction to go in peace and to reenact the story of Hamlet in his remembrance.)

Hamlet, later, realizing that he himself might not be in a state of grace (since he is still planning Claudius' death and since he is in the middle of settling his argument with his brother) refuses the cup from his mother, saying "I dare not yet, by and by." He only receives the cup - drinking the dregs of the poisoned chalice so that Horatio might live - after he has revenged his father and exchanged true reconciliation with Laertes.

Nor is death now a thing to be feared, because Hamlet is reconciled with God. In fact, death is almost to be sought as in the various monks call "Remember thy death!" And Hamlet himself calls for Horatio to tell his story, as we recount to each other the lives of the saints.

Heaven make thee free of it! I follow thee.

I am dead, Horatio. Wretched queen, adieu!

You that look pale and tremble at this chance,

That are but mutes or audience to this act,

Had I but time--as this fell sergeant, death,

Is strict in his arrest--O, I could tell you--

But let it be. Horatio, I am dead;

Thou livest; report me and my cause aright

To the unsatisfied.

Harold Bloom calls the end of Hamlet an apotheosis, and he is quite right to do so. For, far from those tragedies wherein the deaths of the leads are "doubtful" - such as Romeo and Juliet or Macbeth and even to an extent Othello, we are certain sure that Hamlet is going to a place where "flights of angels" might "wing [him] to [his] rest."

Right. Anywho. Must needs block said scene since we're doing it tonight. Enough rambling for today!

Mood: Meh.

Music: Mellow mix a la iTunes

Thoughts: Really, really, really need to clean.

The sporadic ramblings of Emily C. A. Snyder - devoted to God, theatre, writing, and much randominity.

The sporadic ramblings of Emily C. A. Snyder - devoted to God, theatre, writing, and much randominity.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home