Eine Kline Nachthamlet

Kevin Kline's 1990 Broadway Hamlet came in today. Everyone with the over-critical director now: *siiiiiiiiiiiiiigh*. To sum that performance up: "I am a GREAAAAT Shakespeeeeeeearian ACTooooooooorrrrrrr" complete with sentorian tones, implied if not obvious arm upraised, and full membership to the Slow Talkers of America Club. Granted, Kline has excellent diction and beautiful teeth - but where was his humor? Where was his exuberance? Granted that he can summon real tears on cue - but that does not suffice for soliloquizing!

And he played Hamlet as though he were really mad, which made me only realize the futility of making that dramatic choice for the play. If, indeed, Hamlet is mad in fact and not in deed (as, indeed, his own dialogue more than once convinces us that he is "not mad in fact" but has "put on an antic disposition" - hallooo? Dramaturgy 101, anyone?), then the role of Hamlet has no significance. If his actions all spring from a madness that has seized his mind and therefore skewed his will, then his will is not his own and therefore the plot is none of his own doing and thus there is no need for us to watch it because it is not human in origin. Even Oedipus Rex which declares the inexorable will of Fate is a classic because Oedipus pits his free will against a Higher Will. Those plots which rest upon the credo (or excuse), "I had no choice" are lazy plots and barely worth watching. To play Hamlet without a well-formed, nay a better-formed conscience than our own is to un-Hamlet Hamlet.

As to my ever-loving Ophelia. Join with me now: *siiiiiiiiiiiiigh*. What, what, what do people have against her - and for that matter against Gertrude - that no one can seem to do any theatrical good by them? The actress who plays Ophelia is almost always useless until her mad scene and her soliloquy, wherein she often overplays them since up to that point she's had nothing else to do. Gertrude is slightly better off: she at least has the tradition of either playing the dimwit to all the poltical shenanigans, or at least slightly guilty at her "o'erhasty marriage," or at least somewhat maternal if the actress chooses to drink the poisoned cup knowing what it is. But even she is almost always done to pieces in the closet scene where she is lately near-raped by Hamlet. (Nasty, perditious thoughts fly to Freud's grave. God bless his soul, but really!)

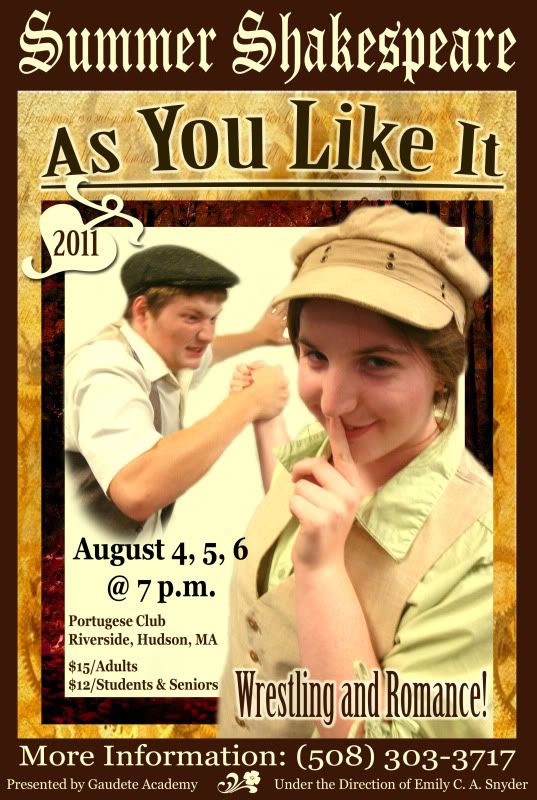

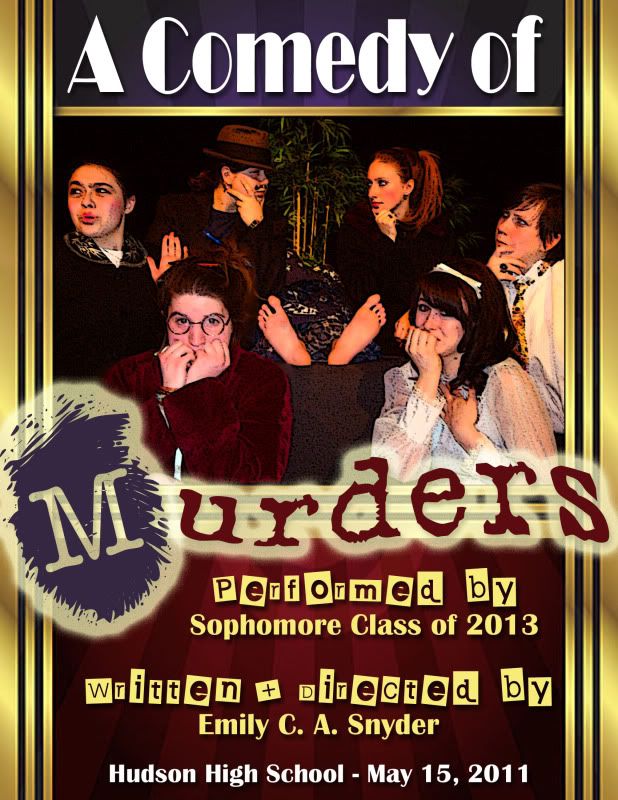

Curious aside on this Oedipal note: on Tuesday night - the night before I fell ill - my family attended a town meeting held by Vote on marriage.org with our representitive. God bless his soul - he says he's Catholic and yet is vociferous about "protecting the right [to marriage] of homosexuals." (Hurrah for Massachusetts. Once again, remember us. Redefinition of a word and now we must beg for the popular vote as though we were serfs? Something is rotten in this state.) Anywho, at the end of the session - which was more or less as fruitless as all my previous conversation with this fellow has been - I cordially thanked him for coming and wished him luck and God's blessing. He had been avoiding my raised hand after my first statement that evening when I had smiling introduced myself as a teacher who thought it best to lay such ground rules such as "whoever is speaking gets to finish his thought before another [i.e., him] could interrupt," but since I was leaving and we were all back to smiling and smiling, he asked where I taught and what. (Nevermind that I had told him at the beginning that I teach religion and so have had this conversation with my students quite a lot over the past few years! But that's alright - I'd hardly remember details myself in such a situation.) Anywho, so I told him religion and drama at HCH. And then I went on - good PR person that I am - to say that we were doing Hamlet next, this summer, and that I'd be sure to send him an invite when it came up. He smiled and said, "Oh, Hamlet! Which one?" And then, before I could think of how to answer him without making him feel like a complete ass, he caught himself and said, "Oh, I was thinking of Shakespeare. I hear the name Hamlet and think Shakespeare." I muttered something about that being quite alright. And, since we had tried to convince him earlier that evening that opening the doors to homosexual marriage were likely to lead to legalizing such unions as incest, polygamy, statutory - bestial, who knows - he laughed, clapped my arm and said, "Now there's incest, eh?" I gave him my rictus smile and said, "Well. That's one way to read it."

Right. Back to my recent epiphany as to why I've been harping so on the depictions of poor Ophelia and Gertrude. I suppose, in part, the reason is partly because I share their sex and being an actress myself their parts intrigue me the more. But also, with Ophelia and Gertrude, Hamlet has the opportunities for actual relationships. Horatio - as I contend - is more his soul. Even were he to go really mad, Horatio would not abandon him. Yet that being so, Hamlet can no more abandon him than he can actually abandon himself. (A side note: Kline's Horatio was given the thankless job of merely being the wide-eyed and somewhat slack-jawed Gee Whiz fellow to Kline's Hamlet. A more generous Hamlet wouldn't be cowed by a strong Horatio, much less by a cleverer grave-digger than he - a part which was also cut down. Everyone now: *siiiiiiiiiiigh*.)

As for Hamlet's other relationships:

His father's dead. Therefore Hamlet's opportunity to know is father rests solely in his ability to carry out his father's dying (or dead?) wish without perdition to his own soul so that he might have hope of a reunited family in Heaven.

His uncle's a murderer, usurper and lech. OK - even if he's the swellest guy ever, Hamlet's in no state to love the fellow. The fact that his new step-dad is who he is and has done what he has done only makes the matter worse. My feeling is, too, that Hamlet probably never liked his father's brother even in life. I can think of one of my own uncles who seems all SORTS of nice, and makes my skin crawl anyway. I imagine that's what Hamlet thought of Claudius even before he knew WHY his skin was crawling every time he saw the guy.

Polonius. Clearly, Hamlet has little respect for this fellow, and one can well understand why. To a real intellectual, Polonius is that sort of tiresome half-wit that thinks more highly of himself than he ought and who - worse - feels the need to show off what little wit he has. Now, granted, Hamlet doesn't hate Polonius, and more Hamlet is himself betraying youthful vainglory in his teasing of Polonius. However, it is interesting to wonder what Hamlet might have been like as Polonius' son-in-law. I imagine he would have suffered through Christmas dinners and come to deal with the old fellow, howevermuch he made sport of him behind his back. During the course of the play, however, he doesn't desire to have a father-son relationship with Polonius. If anything, one might suppose that he'd hope Ophelia would stay away from her father!

Laertes. I imagine that Laertes is more a sporty fellow - that seems to be borne out by what we hear of him, and by Horatio declaring with absolute certainty that Hamlet would lose in the duel with Horatio - and so even if Laertes and Hamlet hung out a lot together, should they have become brothers-in-law, one imagines that on Superbowl Sunday, Hamlet would have made sport of the sport to Laertes' chagrin. I do not doubt that Hamlet thinks well of Laertes and has fondness and respect for him - especially since he has love for his sister that does rival Hamlet's own - but I don't think that the two of them would fall into natural company together. Regardless, they're not given the opportunity.

Rosencrantz and Guilderstern. Hamlet suspects these two from the first, which leads me to think that these fellows are like those freshmen friends one takes that first semester at school in desperation but, finding a little later on those men whose company one actually desires, gladly leaves the first acquaintances as something lethal to the soul. Or, one might think of them as old high school buddies who have continued on in the world, whilst Hamlet has finally quit himself of them and pursued higher thought. Regardless, they share a past, but not one of actual mutual love. To all the world they are congenial but they share nothing in common. Hamlet knows they are spies; they know he knows but hope he does not really know; and one can smile and smile and be a villain. Nope. No relationship with these two!

The various courtiers, guards, etc. C'mon. He's a prince. He's just not going to hang out with Frank, Bernie and Marc the guards, nor less with Osric the behatted. Even the gravedigger, who comes closest to striking up a friendly repartee with our Great Dane ("It is I! Omlette! The Cheese Danish!") is still a servant and thus not going to be stopping by unannounced to Elsinore. (Not that I imagine the gravedigger would want to.)

All of which leads us to his mother and his girlfriend. Both of whom he does have relationships with, and both of whom he does desire relationships with. Let's start with the easier Gertrude, first.

Gertrude. Clearly, Hamlet loves his mom. Loves nearly to the point of distraction. And why should he not? He barely knew his father, his only parent has been his mother, and now his mother has effectively betrayed him by giving all her affection (so it seems) to the slimiest slime of them all. If, Hamlet might feel, Gertrude so easily turns her affection from her fallen husband to another, what might that portend for him? He fears losing his mother to a living death. He fears as well for his mother - there's something "gross and rank in nature" about his uncle that he can't seem to put his finger on. So how could he go to his mother and say, "Yeah. Mom. Your new husband. Um. Look, I just have this feeling go on, OK?" Oh, that's going to be persuasive.

More, the way that I'd like to play it, she's been holding herself more distant from Hamlet out of guilt in herself. By being so complicit in the act, she has not only urged the murderer on, and so indirectly slain her husband, but she has also slain her relationship with her son. What is she to say to Hamlet? "By the by, dear, I've been having an affair with your uncle? Please don't look at me that way!" She remains silent in hopes to keep Hamlet's unknowing love. Yet her silence deepens her guilt because she will not "confess herself to Heaven." So the best she can do is forbid Hamlet to leave Elsinore, in hopes, perhaps, that given time everything will just work itself out. She does not what is best for Hamlet, but what seems best for her - again part of her selfish behaviour that brought her to such a juncture. As well, perhaps, she hopes that something of her son's seeming goodness - and perhaps even his sorrow over old Hamlet! - will rub off on her!

But Hamlet and she do not talk and do not talk and do not talk after she forbids him to leave. And so they don't work anything else, and the gulf between them widens. So that when Hamlet finally confronts her, neither can at first say anything loving to one another. But finally Gertrude is able to do this: she feels the first pangs of her own selfishness, she at least desires the good for Hamlet, she will not allow him to die once he is returned - and she will do more: she will make sure that he is fit for kingship. She will remove Ophelia (of lower birth) from his sphere. She will try to rectify wrongs. But, being so far removed from how to achieve a good by goodness, she tries to do good again by death.

Is Gertrude guilty of old Hamlet's death? Whether she is or not, I think from a purely theatrical point of view, it's far more interesting if Gertrude is Lady Macbeth-like guilty of the affair. If she's just a dupe in all this, then that's dreadful dull to play - and more, then Hamlet's anger with her during the closet scene merely makes him into a beast! If, however, we take his line, "Almost as bad, good mother, as kill a king and marry with his brother" as the idea that - while he may merely be testing her - she is indeed guilty is far more interesting. Certainly, we also see from her other lines about feeling guilt that she has more than hasty marriage on her mind. My thought goes something like this:

* Old Hamlet takes Gertrude, Guinevere-or-Isolde-like, to wed. He's some ten or fifteen years her senior, and yet he is the elder and already distinguished in battle. In fact, if we take the tale that Hamlet is based on, we see that Gertrude is herself of the royal succession, so that to become king, one must either marry Gertrude or be her son. So old Hamlet marries Gertrude, and becomes king. The then goes off for years at a time to secure a larger and larger kingdom - coming home at least long enough for conjugal visits and matters of state.

* Let's imagine, then, that old Hamlet left Claudius at Elsinore to take care of domestic affairs. Claudius seems more politically savvy, more intellectually inclined - at least insofaras political intellecutalism is needed - than his brother. They have very little in common, and perhaps Claudius has always been jealous of old Hamlet - it's not inconceivable. He seems to fear and hold a sort of jealousy towards his nephew, too. Perhaps their father, who Claudius does not seem to mourn himself ("Your father lost his [Claudius!] father/His father lost, lost his"), favoured old Hamlet over Claudius as well. Regardless, Claudius, bright, witty, gay, younger, more apt to make himself likeable to ladies, begins to make himself the companion of the neglected Queen.

* And who knows when their affair began? Or when old Hamlet was aware of it in life - if ever he was? I do not think it's fruitful to imagine our Hamlet Claudius' son - the play would run much differently than it does if that were true - and so let us suppose that Hamlet had at least been born by the time their affair started. Perhaps their affair began with only flirts and such a few years after Hamlet's birth. Perhaps it grew in earnest when Hamlet went to Whittenberg and all seemed safe.

* Perhaps around that time, as old Hamlet stumped around the castle and young Hamlet and all his mirth was gone from it, and Gertrude was nightly summoned to a bed that seemed colder and colder to her, it somehow came into her mind - whether through something she said, or old Hamlet, or something Claudius said in joking - that they might just do away with the king. Wasn't she queen? Couldn't she make Claudius her husband in truth? Mightn't she allay her guilt by lawfully wedding the man she desired? Wasn't it, in truth, a mercy to send the king to his sleep - being, as he was, now weary from long wars, and perhaps a little battered by them? And, after all, wouldn't Claudius make a wonderful king - he who had been practically running the kingdom all these long years?

* So she might whisper to Claudius - sometimes in jest, sometimes in earnest, sometimes in despair, sometimes in fear - and then one day he runs to her, face contorted in the weirdest grin, and says to her that the deed is done. And she, oh God, what might she think? For of a sudden that which she thought she wanted came to her and she found it a black and bloody deed after all.

* Yet she wed. What else could she do? And when her son returned, he saw her weep at the funeral and thought it was for love of the king, and did not know she mourned her own soul. Her marriage bed seemed colder now, if it were possible, than those horrible days when she thought she did not love the old king. But she puts on a face and smiles and smiles and hates herself when her blood runs hot for five minutes all together when Claudius comes to her - hates herself because for all those five minutes, she cannot be warm thereafter or therebefore. She grows more distant from everyone, even from herself, and smiles and smiles and smiles the more.

* Then her son turns lunatic. Polonius says from love of Ophelia - and certain sure, Gertrude knows what lust can drive a man to do. So she stays behind when Claudius orders her to leave. Why should she go? She knows her son best. Knows him better than Claudius ever could. And so watching she sees what the men, only hearing, cannot know: Ophelia bears Hamlet's child. Perhaps Hamlet's son. And suddenly all the hatred she bears herself she turns upon this upstart, this harlot with the virgin's blush. She hears Hamlet screaming for the benefit of the men behind the arras, but she sees him gently kiss Ophelia before he leaves. And she thinks, "Seems, madam? No, I know not seems."

* Claudius is incensed. To England with Hamlet. To the farthest shores with Hamlet. To the moon and the widest spheres with Hamlet. And then to his death in England after the play - wherein even Gertrude grows afraid that she may have been found out. But she is the consummate actress - more than any other on that stage, she can hold her own counsel - and so when Claudius imbecile-like leaps up in fright, she keeps her peace and summons Hamlet.

* What does she intend? To berate him? To perhaps make him feel ashamed enough to admit that he ought to love Claudius? To make him say that he dallied with a girl of lower birth and now repents it? To come to such a place that Gertrude will feel justified - at long, long last - with what she herself has done? In comes Hamlet, gun still in hand from having nearly killed the king, so that all her resolve melts and she dives for the phone, for aid, thinking that the instinct to murder might be genetic. If she could kill, might not Hamlet do so likewise?

* And so he does. But stupid old foolish Polonius falls, and Hamlet - in shock at his deed - does not fly at his mother, but breaks down like a child. And now we have a mother and a son, the son begging his mother to see with purer eyes what she never saw before, the goodness of his fallen father. He grows hysterical with tears so that he might, at her lightest touch, forget all his action and become a mere babe again when

* The ghost appears. Wherefore does he come? And does only Hamlet see him? I think he must, given the text, but might not Gertrude feel something other there as well - something she desperately, desperately wants to deny, someone she has already denied, betrayed, Judas-like to his death? Yet it is this visitation that finally softens her heart and puts her back on the path of justification - no matter how far she has strayed. She will do well for her son - although her feelings towards all others is muddied.

* Perhaps Hamlet leaves his image of the old king with her. Perhaps she is looking on this when Claudius bursts in asking where "your son" has gone. And, true to her word, she does not betray Hamlet, but looks Claudius in the eye and tells him that Hamlet is mad, and though he slew Polonius he is not guilty of his actions. Alas, the rift between sometime husband and wife has grown wide indeed and Claudius determines to kill Hamlet - no matter what Gertrude desires.

* Hamlet caught, sent away, perhaps to his death - although perhaps Gertrude has good reason to hope that her Hamlet is far more clever than ridiculous Rosencrantz and Guilderstern - Gertrude is left with only Claudius and Ophelia of all this sorry mess. What might she think? Ophelia, pregnant with her own grandchild, feigning as Hamlet once feigned, madness - which Gertrude being "in" on Hamlet's lunacy must now surely recognize. She does not at first want to see Ophelia, and then on seeing her, Ophelia is rather pointed whenever she addresses the Queen. "My brother shall hear of this. There's rue for you. But you must wear yours with a difference. Lord, we know who we are but know not what we may be."

* Yet when Laertes enters with rebellion, when it looks as though all Denmark might make this upstart king, and then with another rightful heir lying beneath Ophelia's breast - when word comes that Hamlet is returned, having surely learned by this time about the whole court's duplicity - what might Gertrude do to keep the throne for her son and her son only? What might Gertrude do now that her son is returned and might marry another more favorably. Well she wots what happens when brothers who see themselves as bastardized are free to seduce innocent maids in the court. Her Hamlet shall not suffer that, too. And so she calmly goes, with guards, plucks Ophelia from her place, and herself holds the girl beneath the water. (What if Hamlet had stayed? What if Gertrude and he had, through the ghost's intercession, come to mutual confession? What if she had not been neglected again to the vices of that vile court?)

* The actress returns at the graveside, "Sweets to the sweet, farewell." She can spare such words now when there are none to harm her. But then her son appears and she hears his heart wrenched out, "I LOVED OPHELIA!" And her heart begins to break again. Claudius and Laertes have set the fatal duel. She sees the pearl. She knows her husband's treachery as she knows her own. She sees but one opportunity. And perhaps God would have mercy on her soul and see it not as a suicide but a sacrifice? And perhaps - although I do not know - the ghost appears when first the poisoned pearl is put in glass - and she sees him and sees her own sins and that prompts her to the one selfless deed she has done this own play. And that single, selfless act may be enough to join her to her first husband in purgation, where all may be reconciled. Amen.

So much for Gertrude! Now to the other.

Ophelia. Right. Less is known of her, of course. We might suppose her five years or so Hamlet's junior. About the same of Laertes. And Polonius, although frequently shown to be an exceedingly old man, may be more late middle-aged. He is a fool; not necessarily a dotard. Now, the question becomes when did Ophelia and Hamlet first take up? And yet, perhaps a better question would be, when did she first love him?

* Let's imagine Ophelia at ten, seeing the brave prince practicing his foil with her own brother, or both with the master. Hamlet's turn is up and he comes to the bench where she's sitting to get a drink. Sitting by her, he ruffles her hair and proceeds to verbally tear apart her brother's fencing lesson, much to her mirth. And to his mirth, she responds, hesitantly at first, with riposte for riposte. She, of course, is from that moment infatuated. He, alas, thinks little of her when he thinks of her at all.

* Five years pass, and Hamlet goes to Whittenberg. But when he returns he sees Ophelia again and, although only a school year has gone by, he seems to have new eyes to see what might have been apparent all these years. Here's a lovely girl, with whom he can converse with ease, who entertains him nearly as well as his school-fellows, if in a different manner than their ribald humour. She asks him about philosophy and he, being of an active mind, spends the summer tutoring her. His interest is piqued - but he hardly dares to think of much more. He is a prince. She is still very young.

* Another school year comes and goes before Hamlet returns. Some week or so into his summer stay he sees Ophelia again. (Unbeknownst to him, she has been following his every move and ducking out of the way again. But this time, she has decided to stand her ground.) "How do you, pretty maid?" he asks - unsure about whether to treat her as the ten year old he knew or like any of the other young ladies he has known. She engages him immediately in intellectual conversation. She has been reading Aristotle, Socrates, Plato, Cicero - only in translation, but what of that? Has she read Augustine? Acquinas? Any of the great moderns? She has not. But would be most eager to learn. And so another summer session begins, sitting huddled together on benches, stealing moments, sharing secrets - light, common ones, nothing too daring yet - until that day when suddenly in the middle of some difficult Greek or Roman passage, one or the other swiftly descends upon the other and they kiss.

* Who knows who breaks off first? Regardless, Hamlet feels like a cad afterwards. Here he had just shaken off Guildenstern and Rosencrantz, those leches, and truly begun to purify his mind, and he no sooner returns home than seduces his chamberlain's daughter. It's like something out of a bad folk song. As for Ophelia, she's enraptured. It's as good as an engagement to her. She lingers over the memory of it for nights on end, until such a time comes when she realizes that she hasn't seen Hamlet alone for more than a week, two, three. And the summer's end is fast approaching.

* And then, perhaps a week before Hamlet is to embark, he comes to her chambers, throws pebbles at the window, until she comes down to the courtyard just beneath. They talk. Or say rather, Hamlet jabbers, grabs at his hair, paces about, laughs and blushes and looks at anything but her, and she waits patiently for him to finish, or to sit beside her, or to decide what he actually means. At long, long last, (but Ophelia is patient; she's never loved anyone else to learn when she can be impatient), Hamlet sits beside her and asks forgiveness for kissing her. "Kissed me?" she smiles. "I thought I kissed you." "All the worse," he replies. "How can a good thing be worse?" she retorts. And leaning forward again, she kisses him - there is no doubt she began it this time - and when she pulls back, she says, "I do not fear thee." "Thou shouldst fear me," he answers. "If thou hast sense about thee." "Then am I senseless," she whispers and what happens between them then - although innocent - had best be left to the folds of time.

* Suppose Hamlet goes along with the relationship because he need not fear himself being so often so far from her that he is like to do her no harm besides a few kisses, and no harm to any other woman for his word given is good and he will not unfaithful be. Suppose, too, Hamlet sees in Ophelia the glass of perfection, of innocence, which even a brief year with the Rosencrantzes and Guildersterns of the world have stripped from him (to what extent, I do not know) - and so he sees in her his salvation. What though she be of lowly birth? He would not be king for years and years and years for - so far as he knows - his father is healthy. More, perhaps he imagines, either if he become king he could change the laws, or else if he be the scholar prince merely, his son would still be of noble birth to assume the crown. And more, he does not like to think on her birth, or if he thinks on it as all, it only grows to his romance of her purity - that she is like a Madonna more in that regard.

* Then his father dies. Gertrude writes of it to him. Ophelia writes to him - but a briefer note. More notes come. None comforting. He returns - there's no chance to catch Ophelia alone, to lay his head chastely against her bosom, to pour out his tears upon her heart. Matters of state must be attended to. The election is held and Claudius will be king. And Hamlet must stand in attendance and smile and smile and perhaps even have a part in laying his own rightful scepter in the usurper's crown. He longs to tell Ophelia of his misgivings, but Polonius keeps him forever busy with details of ceremony. And then the priest does the same as, with a shock, Hamlet finds he must give his own mother away in marriage. Does he pass Ophelia as he walks by her down the aisle? Does he dare look at her? I think he must. And she at him. And though they have not spoken, much is said in that glance, for she is now many years older than she had been when first they came together. Questions too numerous to name much less to catalogue flit across their mirrored features...and all is lost, lost, lost.

* The Ghost comes. Ophelia knows nothing of it, for that same night she is lying disconsolate in her room, sprawled across her bed, biting back tears, keeping tears carefully from the letters she has had from Hamlet. Laertes has disavowed Hamlet's love, and perhaps he would know for men will speak differently to each other then in woman's company. And Polonius has forbidden her to see Hamlet - but what can he know of anything, except the game political? She has no doubt he intends something political with her. She had flown to Hamlet's chamber as soon as she was able, but had found him gone, she knew not where - nor would she have thought to go on the ramparts to search for him, for none but guards went there. His latest letter lies in her hand as she looks the window at the thin, grey clouds hide and reveal and hide the gibbous moon that stands precious half in shadow, half light.

* Shouts outside. Perhaps she even hears the reverberation of the old king's voice as the men all swear. And not twenty minutes later, a clattering upon the steps just outside her own room. She flings open the door to see who is going to rudesome past and sees Hamlet descending, laughing as though a boy on Christmas morn, coming last down the winding stair. He catches sight of her, sweeps her into an embrace, whirls with her into the room and - caught so in the heat of passion, one with the hope of hot revenge, one with the fury at a love denied - that neither think to temper their desires, and when they wake to what they have done later that night, all they both can think is, "What have we done?"

* If left there with their guilt alone, who knows how the story might run? But no sooner have they looked at each other in shame, in desire, in disgust, than they hear Polonius' voice without giving order to Reynaldo. His voice draws nearer and nearer. There is no escape. Hamlet must hide. Ophelia throws on her night dress, pulls up the covers on her bed, throws Hamlet's things behind the curtain where he stands. In comes Polonius, and before he can get his wits about him, Ophelia runs to him with a strange story touching on the Lord Hamlet, which Polonius - ever eager for advancement - seizes.

* What had been the cause for much giggling and smirking one to the other as Polonius wondered over this strange story becomes quite serious when he drags it before the King and Queen. And all of a sudden Ophelia finds herself set up to do the same lying disservice to Hamlet as she has just done to her father. Once again, she is bound to absent herself from Hamlet - but this time there would be no going back, no stolen kisses - not once she makes him understand the full gravity of all they had done together.

* "My honored lord, I have gives that I have l-longed long to redeliver to thee." "No, no" he says, frightened now - he had been so eager to see the one with whom he might be wholly himself. "I never gave you aught." And then she puts her hand to her stomach - for much time has passed, and she is sure now - "My honored lord...you know right well you did." Then louder, for the benefit of those listening, "And with them of such sweet breath as made the giving more rich. Their perfume lost take these again, for to the mind...rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind. There my lord." He's taken aback. He can hardly speak. And so he falls into the first sort of conversation he's ever had with her - philosophy, questions of beauty and chastity, meant to make her feel ashamed, to share in the shame he most profoundly feels. For it's his fault that Ophelia, the paragon of virtue, the model of chastity, the monument to innocence, has been spoilt. He tries to deny it, "I loved you..." whispered, tense, "once?" From her, with bitterness, "My lord, you did make me believe it." From him, terrified, "You should not have believe me." From her, pained, "I was the more deceived." And then from him again, all distract for what sort of child could he beget? What could vice beget? Is not his whole course from the ghost to restore goodness and not vice to the marriage beds of Denmark? "Why wouldst thou be a breeder of sinners? I could myself accuse me of more things that it were better my mother had not bourne me." He backs away from her when she would come near, because he feels himself the weight of his "too, too sullied flesh." And finally, realizing that if he goes through with his action, he will lose her and the child too, he warns her, "To a nunnery go, and quickly too. Farewell."

* They do not speak again after that until the Mousetrap. And yet when they do meet there's another dynamic at work. She tries to be the Ice Queen. He tries to be the Rougish Winking Knave. And yet while the play within a play progresses, there are moments of true tenderness, of aching rawness, moments when they almost say, "I'm sorry" - but that time constrains them. "Tis brief, my lord." "As woman's love." "That's a fair thought to lie between a woman's legs." "What is, my lord?" (Embarassment, he's gone too far.) "...Nothing." And then when she's taken off, dragged away by her father, a moment - just a moment - a look - an unspoken exchange - and Hamlet's future happiness slips from him like that.

* The remainder is played out separately. The lovers are not allowed to meet again. Ophelia, realizing as she sees her father's dead body taken out as Hamlet is led away enchained, that her own life is in danger now that there's none in the court to protect her, chooses Hamlet's mode of madness. For who would kill a mad woman who knows nothing, who cannot remember that fateful Moustrap, who certainly did not know what it portended? Everything she says is about her father, no? But when her brother comes she tries - how does she try! - to make him look in her eyes, see the sanity there. But Laertes is caught up with a father's grief, and with Claudius' seeming sweetness, that he does not listen to any reason whatsoever. And so he does not see Gertrude's patient stillness, like a panther before it strikes, or a cobra when it coils, but lets Ophelia be led away by guards whilst he goes to learn how best to damn his own soul.

* How should Horatio break to Hamlet Ophelia's death? He brings him to the graveyard. He bites his tongue when Hamlet whispers to Yorick's skull with a tenderness, a sadness, a bitter hope, "Go. Make her laugh at that." And then the funeral comes, what with one thing and another, Hamlet puzzles together the Gravedigger's riddles and knows what only one other still living knows: that not only Ophelia died, but his unborn child as well.

* And perhaps this small saint in Heaven is the one who finally intercedes for his father, when Hamlet realizes that there is "a certain Providence in the fall of every sparrow...the readiness is all. Let be." Hamlet, with all he loves now either in Heaven or hopefully bound for it, goes to the clumsy trap Claudius and Laertes have set out, ready to die - freed at last to carry out the ghost's revenge at such an opportunity - freed at last to have no fear for his life by surrendering all his life to One far greater than himself. This, then, is our apotheosis. And if the rest is silence, it's only because no ghost need come back to right another wrong. It is done.

Anywho those are my thoughts. Yup yup yup.

Mood: OJ is a balm unto my throat

Music: "Keep Myself Awake" a la the first Buffy album, although I use it on the current Hamlet Inspirational CD.

Thought: Too many to judge by the length of this post!

Kevin Kline's 1990 Broadway Hamlet came in today. Everyone with the over-critical director now: *siiiiiiiiiiiiiigh*. To sum that performance up: "I am a GREAAAAT Shakespeeeeeeearian ACTooooooooorrrrrrr" complete with sentorian tones, implied if not obvious arm upraised, and full membership to the Slow Talkers of America Club. Granted, Kline has excellent diction and beautiful teeth - but where was his humor? Where was his exuberance? Granted that he can summon real tears on cue - but that does not suffice for soliloquizing!

And he played Hamlet as though he were really mad, which made me only realize the futility of making that dramatic choice for the play. If, indeed, Hamlet is mad in fact and not in deed (as, indeed, his own dialogue more than once convinces us that he is "not mad in fact" but has "put on an antic disposition" - hallooo? Dramaturgy 101, anyone?), then the role of Hamlet has no significance. If his actions all spring from a madness that has seized his mind and therefore skewed his will, then his will is not his own and therefore the plot is none of his own doing and thus there is no need for us to watch it because it is not human in origin. Even Oedipus Rex which declares the inexorable will of Fate is a classic because Oedipus pits his free will against a Higher Will. Those plots which rest upon the credo (or excuse), "I had no choice" are lazy plots and barely worth watching. To play Hamlet without a well-formed, nay a better-formed conscience than our own is to un-Hamlet Hamlet.

As to my ever-loving Ophelia. Join with me now: *siiiiiiiiiiiiigh*. What, what, what do people have against her - and for that matter against Gertrude - that no one can seem to do any theatrical good by them? The actress who plays Ophelia is almost always useless until her mad scene and her soliloquy, wherein she often overplays them since up to that point she's had nothing else to do. Gertrude is slightly better off: she at least has the tradition of either playing the dimwit to all the poltical shenanigans, or at least slightly guilty at her "o'erhasty marriage," or at least somewhat maternal if the actress chooses to drink the poisoned cup knowing what it is. But even she is almost always done to pieces in the closet scene where she is lately near-raped by Hamlet. (Nasty, perditious thoughts fly to Freud's grave. God bless his soul, but really!)

Curious aside on this Oedipal note: on Tuesday night - the night before I fell ill - my family attended a town meeting held by Vote on marriage.org with our representitive. God bless his soul - he says he's Catholic and yet is vociferous about "protecting the right [to marriage] of homosexuals." (Hurrah for Massachusetts. Once again, remember us. Redefinition of a word and now we must beg for the popular vote as though we were serfs? Something is rotten in this state.) Anywho, at the end of the session - which was more or less as fruitless as all my previous conversation with this fellow has been - I cordially thanked him for coming and wished him luck and God's blessing. He had been avoiding my raised hand after my first statement that evening when I had smiling introduced myself as a teacher who thought it best to lay such ground rules such as "whoever is speaking gets to finish his thought before another [i.e., him] could interrupt," but since I was leaving and we were all back to smiling and smiling, he asked where I taught and what. (Nevermind that I had told him at the beginning that I teach religion and so have had this conversation with my students quite a lot over the past few years! But that's alright - I'd hardly remember details myself in such a situation.) Anywho, so I told him religion and drama at HCH. And then I went on - good PR person that I am - to say that we were doing Hamlet next, this summer, and that I'd be sure to send him an invite when it came up. He smiled and said, "Oh, Hamlet! Which one?" And then, before I could think of how to answer him without making him feel like a complete ass, he caught himself and said, "Oh, I was thinking of Shakespeare. I hear the name Hamlet and think Shakespeare." I muttered something about that being quite alright. And, since we had tried to convince him earlier that evening that opening the doors to homosexual marriage were likely to lead to legalizing such unions as incest, polygamy, statutory - bestial, who knows - he laughed, clapped my arm and said, "Now there's incest, eh?" I gave him my rictus smile and said, "Well. That's one way to read it."

Right. Back to my recent epiphany as to why I've been harping so on the depictions of poor Ophelia and Gertrude. I suppose, in part, the reason is partly because I share their sex and being an actress myself their parts intrigue me the more. But also, with Ophelia and Gertrude, Hamlet has the opportunities for actual relationships. Horatio - as I contend - is more his soul. Even were he to go really mad, Horatio would not abandon him. Yet that being so, Hamlet can no more abandon him than he can actually abandon himself. (A side note: Kline's Horatio was given the thankless job of merely being the wide-eyed and somewhat slack-jawed Gee Whiz fellow to Kline's Hamlet. A more generous Hamlet wouldn't be cowed by a strong Horatio, much less by a cleverer grave-digger than he - a part which was also cut down. Everyone now: *siiiiiiiiiiigh*.)

As for Hamlet's other relationships:

All of which leads us to his mother and his girlfriend. Both of whom he does have relationships with, and both of whom he does desire relationships with. Let's start with the easier Gertrude, first.

More, the way that I'd like to play it, she's been holding herself more distant from Hamlet out of guilt in herself. By being so complicit in the act, she has not only urged the murderer on, and so indirectly slain her husband, but she has also slain her relationship with her son. What is she to say to Hamlet? "By the by, dear, I've been having an affair with your uncle? Please don't look at me that way!" She remains silent in hopes to keep Hamlet's unknowing love. Yet her silence deepens her guilt because she will not "confess herself to Heaven." So the best she can do is forbid Hamlet to leave Elsinore, in hopes, perhaps, that given time everything will just work itself out. She does not what is best for Hamlet, but what seems best for her - again part of her selfish behaviour that brought her to such a juncture. As well, perhaps, she hopes that something of her son's seeming goodness - and perhaps even his sorrow over old Hamlet! - will rub off on her!

But Hamlet and she do not talk and do not talk and do not talk after she forbids him to leave. And so they don't work anything else, and the gulf between them widens. So that when Hamlet finally confronts her, neither can at first say anything loving to one another. But finally Gertrude is able to do this: she feels the first pangs of her own selfishness, she at least desires the good for Hamlet, she will not allow him to die once he is returned - and she will do more: she will make sure that he is fit for kingship. She will remove Ophelia (of lower birth) from his sphere. She will try to rectify wrongs. But, being so far removed from how to achieve a good by goodness, she tries to do good again by death.

Is Gertrude guilty of old Hamlet's death? Whether she is or not, I think from a purely theatrical point of view, it's far more interesting if Gertrude is Lady Macbeth-like guilty of the affair. If she's just a dupe in all this, then that's dreadful dull to play - and more, then Hamlet's anger with her during the closet scene merely makes him into a beast! If, however, we take his line, "Almost as bad, good mother, as kill a king and marry with his brother" as the idea that - while he may merely be testing her - she is indeed guilty is far more interesting. Certainly, we also see from her other lines about feeling guilt that she has more than hasty marriage on her mind. My thought goes something like this:

* Old Hamlet takes Gertrude, Guinevere-or-Isolde-like, to wed. He's some ten or fifteen years her senior, and yet he is the elder and already distinguished in battle. In fact, if we take the tale that Hamlet is based on, we see that Gertrude is herself of the royal succession, so that to become king, one must either marry Gertrude or be her son. So old Hamlet marries Gertrude, and becomes king. The then goes off for years at a time to secure a larger and larger kingdom - coming home at least long enough for conjugal visits and matters of state.

* Let's imagine, then, that old Hamlet left Claudius at Elsinore to take care of domestic affairs. Claudius seems more politically savvy, more intellectually inclined - at least insofaras political intellecutalism is needed - than his brother. They have very little in common, and perhaps Claudius has always been jealous of old Hamlet - it's not inconceivable. He seems to fear and hold a sort of jealousy towards his nephew, too. Perhaps their father, who Claudius does not seem to mourn himself ("Your father lost his [Claudius!] father/His father lost, lost his"), favoured old Hamlet over Claudius as well. Regardless, Claudius, bright, witty, gay, younger, more apt to make himself likeable to ladies, begins to make himself the companion of the neglected Queen.

* And who knows when their affair began? Or when old Hamlet was aware of it in life - if ever he was? I do not think it's fruitful to imagine our Hamlet Claudius' son - the play would run much differently than it does if that were true - and so let us suppose that Hamlet had at least been born by the time their affair started. Perhaps their affair began with only flirts and such a few years after Hamlet's birth. Perhaps it grew in earnest when Hamlet went to Whittenberg and all seemed safe.

* Perhaps around that time, as old Hamlet stumped around the castle and young Hamlet and all his mirth was gone from it, and Gertrude was nightly summoned to a bed that seemed colder and colder to her, it somehow came into her mind - whether through something she said, or old Hamlet, or something Claudius said in joking - that they might just do away with the king. Wasn't she queen? Couldn't she make Claudius her husband in truth? Mightn't she allay her guilt by lawfully wedding the man she desired? Wasn't it, in truth, a mercy to send the king to his sleep - being, as he was, now weary from long wars, and perhaps a little battered by them? And, after all, wouldn't Claudius make a wonderful king - he who had been practically running the kingdom all these long years?

* So she might whisper to Claudius - sometimes in jest, sometimes in earnest, sometimes in despair, sometimes in fear - and then one day he runs to her, face contorted in the weirdest grin, and says to her that the deed is done. And she, oh God, what might she think? For of a sudden that which she thought she wanted came to her and she found it a black and bloody deed after all.

* Yet she wed. What else could she do? And when her son returned, he saw her weep at the funeral and thought it was for love of the king, and did not know she mourned her own soul. Her marriage bed seemed colder now, if it were possible, than those horrible days when she thought she did not love the old king. But she puts on a face and smiles and smiles and hates herself when her blood runs hot for five minutes all together when Claudius comes to her - hates herself because for all those five minutes, she cannot be warm thereafter or therebefore. She grows more distant from everyone, even from herself, and smiles and smiles and smiles the more.

* Then her son turns lunatic. Polonius says from love of Ophelia - and certain sure, Gertrude knows what lust can drive a man to do. So she stays behind when Claudius orders her to leave. Why should she go? She knows her son best. Knows him better than Claudius ever could. And so watching she sees what the men, only hearing, cannot know: Ophelia bears Hamlet's child. Perhaps Hamlet's son. And suddenly all the hatred she bears herself she turns upon this upstart, this harlot with the virgin's blush. She hears Hamlet screaming for the benefit of the men behind the arras, but she sees him gently kiss Ophelia before he leaves. And she thinks, "Seems, madam? No, I know not seems."

* Claudius is incensed. To England with Hamlet. To the farthest shores with Hamlet. To the moon and the widest spheres with Hamlet. And then to his death in England after the play - wherein even Gertrude grows afraid that she may have been found out. But she is the consummate actress - more than any other on that stage, she can hold her own counsel - and so when Claudius imbecile-like leaps up in fright, she keeps her peace and summons Hamlet.

* What does she intend? To berate him? To perhaps make him feel ashamed enough to admit that he ought to love Claudius? To make him say that he dallied with a girl of lower birth and now repents it? To come to such a place that Gertrude will feel justified - at long, long last - with what she herself has done? In comes Hamlet, gun still in hand from having nearly killed the king, so that all her resolve melts and she dives for the phone, for aid, thinking that the instinct to murder might be genetic. If she could kill, might not Hamlet do so likewise?

* And so he does. But stupid old foolish Polonius falls, and Hamlet - in shock at his deed - does not fly at his mother, but breaks down like a child. And now we have a mother and a son, the son begging his mother to see with purer eyes what she never saw before, the goodness of his fallen father. He grows hysterical with tears so that he might, at her lightest touch, forget all his action and become a mere babe again when

* The ghost appears. Wherefore does he come? And does only Hamlet see him? I think he must, given the text, but might not Gertrude feel something other there as well - something she desperately, desperately wants to deny, someone she has already denied, betrayed, Judas-like to his death? Yet it is this visitation that finally softens her heart and puts her back on the path of justification - no matter how far she has strayed. She will do well for her son - although her feelings towards all others is muddied.

* Perhaps Hamlet leaves his image of the old king with her. Perhaps she is looking on this when Claudius bursts in asking where "your son" has gone. And, true to her word, she does not betray Hamlet, but looks Claudius in the eye and tells him that Hamlet is mad, and though he slew Polonius he is not guilty of his actions. Alas, the rift between sometime husband and wife has grown wide indeed and Claudius determines to kill Hamlet - no matter what Gertrude desires.

* Hamlet caught, sent away, perhaps to his death - although perhaps Gertrude has good reason to hope that her Hamlet is far more clever than ridiculous Rosencrantz and Guilderstern - Gertrude is left with only Claudius and Ophelia of all this sorry mess. What might she think? Ophelia, pregnant with her own grandchild, feigning as Hamlet once feigned, madness - which Gertrude being "in" on Hamlet's lunacy must now surely recognize. She does not at first want to see Ophelia, and then on seeing her, Ophelia is rather pointed whenever she addresses the Queen. "My brother shall hear of this. There's rue for you. But you must wear yours with a difference. Lord, we know who we are but know not what we may be."

* Yet when Laertes enters with rebellion, when it looks as though all Denmark might make this upstart king, and then with another rightful heir lying beneath Ophelia's breast - when word comes that Hamlet is returned, having surely learned by this time about the whole court's duplicity - what might Gertrude do to keep the throne for her son and her son only? What might Gertrude do now that her son is returned and might marry another more favorably. Well she wots what happens when brothers who see themselves as bastardized are free to seduce innocent maids in the court. Her Hamlet shall not suffer that, too. And so she calmly goes, with guards, plucks Ophelia from her place, and herself holds the girl beneath the water. (What if Hamlet had stayed? What if Gertrude and he had, through the ghost's intercession, come to mutual confession? What if she had not been neglected again to the vices of that vile court?)

* The actress returns at the graveside, "Sweets to the sweet, farewell." She can spare such words now when there are none to harm her. But then her son appears and she hears his heart wrenched out, "I LOVED OPHELIA!" And her heart begins to break again. Claudius and Laertes have set the fatal duel. She sees the pearl. She knows her husband's treachery as she knows her own. She sees but one opportunity. And perhaps God would have mercy on her soul and see it not as a suicide but a sacrifice? And perhaps - although I do not know - the ghost appears when first the poisoned pearl is put in glass - and she sees him and sees her own sins and that prompts her to the one selfless deed she has done this own play. And that single, selfless act may be enough to join her to her first husband in purgation, where all may be reconciled. Amen.

So much for Gertrude! Now to the other.

* Let's imagine Ophelia at ten, seeing the brave prince practicing his foil with her own brother, or both with the master. Hamlet's turn is up and he comes to the bench where she's sitting to get a drink. Sitting by her, he ruffles her hair and proceeds to verbally tear apart her brother's fencing lesson, much to her mirth. And to his mirth, she responds, hesitantly at first, with riposte for riposte. She, of course, is from that moment infatuated. He, alas, thinks little of her when he thinks of her at all.

* Five years pass, and Hamlet goes to Whittenberg. But when he returns he sees Ophelia again and, although only a school year has gone by, he seems to have new eyes to see what might have been apparent all these years. Here's a lovely girl, with whom he can converse with ease, who entertains him nearly as well as his school-fellows, if in a different manner than their ribald humour. She asks him about philosophy and he, being of an active mind, spends the summer tutoring her. His interest is piqued - but he hardly dares to think of much more. He is a prince. She is still very young.

* Another school year comes and goes before Hamlet returns. Some week or so into his summer stay he sees Ophelia again. (Unbeknownst to him, she has been following his every move and ducking out of the way again. But this time, she has decided to stand her ground.) "How do you, pretty maid?" he asks - unsure about whether to treat her as the ten year old he knew or like any of the other young ladies he has known. She engages him immediately in intellectual conversation. She has been reading Aristotle, Socrates, Plato, Cicero - only in translation, but what of that? Has she read Augustine? Acquinas? Any of the great moderns? She has not. But would be most eager to learn. And so another summer session begins, sitting huddled together on benches, stealing moments, sharing secrets - light, common ones, nothing too daring yet - until that day when suddenly in the middle of some difficult Greek or Roman passage, one or the other swiftly descends upon the other and they kiss.

* Who knows who breaks off first? Regardless, Hamlet feels like a cad afterwards. Here he had just shaken off Guildenstern and Rosencrantz, those leches, and truly begun to purify his mind, and he no sooner returns home than seduces his chamberlain's daughter. It's like something out of a bad folk song. As for Ophelia, she's enraptured. It's as good as an engagement to her. She lingers over the memory of it for nights on end, until such a time comes when she realizes that she hasn't seen Hamlet alone for more than a week, two, three. And the summer's end is fast approaching.

* And then, perhaps a week before Hamlet is to embark, he comes to her chambers, throws pebbles at the window, until she comes down to the courtyard just beneath. They talk. Or say rather, Hamlet jabbers, grabs at his hair, paces about, laughs and blushes and looks at anything but her, and she waits patiently for him to finish, or to sit beside her, or to decide what he actually means. At long, long last, (but Ophelia is patient; she's never loved anyone else to learn when she can be impatient), Hamlet sits beside her and asks forgiveness for kissing her. "Kissed me?" she smiles. "I thought I kissed you." "All the worse," he replies. "How can a good thing be worse?" she retorts. And leaning forward again, she kisses him - there is no doubt she began it this time - and when she pulls back, she says, "I do not fear thee." "Thou shouldst fear me," he answers. "If thou hast sense about thee." "Then am I senseless," she whispers and what happens between them then - although innocent - had best be left to the folds of time.

* Suppose Hamlet goes along with the relationship because he need not fear himself being so often so far from her that he is like to do her no harm besides a few kisses, and no harm to any other woman for his word given is good and he will not unfaithful be. Suppose, too, Hamlet sees in Ophelia the glass of perfection, of innocence, which even a brief year with the Rosencrantzes and Guildersterns of the world have stripped from him (to what extent, I do not know) - and so he sees in her his salvation. What though she be of lowly birth? He would not be king for years and years and years for - so far as he knows - his father is healthy. More, perhaps he imagines, either if he become king he could change the laws, or else if he be the scholar prince merely, his son would still be of noble birth to assume the crown. And more, he does not like to think on her birth, or if he thinks on it as all, it only grows to his romance of her purity - that she is like a Madonna more in that regard.

* Then his father dies. Gertrude writes of it to him. Ophelia writes to him - but a briefer note. More notes come. None comforting. He returns - there's no chance to catch Ophelia alone, to lay his head chastely against her bosom, to pour out his tears upon her heart. Matters of state must be attended to. The election is held and Claudius will be king. And Hamlet must stand in attendance and smile and smile and perhaps even have a part in laying his own rightful scepter in the usurper's crown. He longs to tell Ophelia of his misgivings, but Polonius keeps him forever busy with details of ceremony. And then the priest does the same as, with a shock, Hamlet finds he must give his own mother away in marriage. Does he pass Ophelia as he walks by her down the aisle? Does he dare look at her? I think he must. And she at him. And though they have not spoken, much is said in that glance, for she is now many years older than she had been when first they came together. Questions too numerous to name much less to catalogue flit across their mirrored features...and all is lost, lost, lost.

* The Ghost comes. Ophelia knows nothing of it, for that same night she is lying disconsolate in her room, sprawled across her bed, biting back tears, keeping tears carefully from the letters she has had from Hamlet. Laertes has disavowed Hamlet's love, and perhaps he would know for men will speak differently to each other then in woman's company. And Polonius has forbidden her to see Hamlet - but what can he know of anything, except the game political? She has no doubt he intends something political with her. She had flown to Hamlet's chamber as soon as she was able, but had found him gone, she knew not where - nor would she have thought to go on the ramparts to search for him, for none but guards went there. His latest letter lies in her hand as she looks the window at the thin, grey clouds hide and reveal and hide the gibbous moon that stands precious half in shadow, half light.

* Shouts outside. Perhaps she even hears the reverberation of the old king's voice as the men all swear. And not twenty minutes later, a clattering upon the steps just outside her own room. She flings open the door to see who is going to rudesome past and sees Hamlet descending, laughing as though a boy on Christmas morn, coming last down the winding stair. He catches sight of her, sweeps her into an embrace, whirls with her into the room and - caught so in the heat of passion, one with the hope of hot revenge, one with the fury at a love denied - that neither think to temper their desires, and when they wake to what they have done later that night, all they both can think is, "What have we done?"

* If left there with their guilt alone, who knows how the story might run? But no sooner have they looked at each other in shame, in desire, in disgust, than they hear Polonius' voice without giving order to Reynaldo. His voice draws nearer and nearer. There is no escape. Hamlet must hide. Ophelia throws on her night dress, pulls up the covers on her bed, throws Hamlet's things behind the curtain where he stands. In comes Polonius, and before he can get his wits about him, Ophelia runs to him with a strange story touching on the Lord Hamlet, which Polonius - ever eager for advancement - seizes.

* What had been the cause for much giggling and smirking one to the other as Polonius wondered over this strange story becomes quite serious when he drags it before the King and Queen. And all of a sudden Ophelia finds herself set up to do the same lying disservice to Hamlet as she has just done to her father. Once again, she is bound to absent herself from Hamlet - but this time there would be no going back, no stolen kisses - not once she makes him understand the full gravity of all they had done together.

* "My honored lord, I have gives that I have l-longed long to redeliver to thee." "No, no" he says, frightened now - he had been so eager to see the one with whom he might be wholly himself. "I never gave you aught." And then she puts her hand to her stomach - for much time has passed, and she is sure now - "My honored lord...you know right well you did." Then louder, for the benefit of those listening, "And with them of such sweet breath as made the giving more rich. Their perfume lost take these again, for to the mind...rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind. There my lord." He's taken aback. He can hardly speak. And so he falls into the first sort of conversation he's ever had with her - philosophy, questions of beauty and chastity, meant to make her feel ashamed, to share in the shame he most profoundly feels. For it's his fault that Ophelia, the paragon of virtue, the model of chastity, the monument to innocence, has been spoilt. He tries to deny it, "I loved you..." whispered, tense, "once?" From her, with bitterness, "My lord, you did make me believe it." From him, terrified, "You should not have believe me." From her, pained, "I was the more deceived." And then from him again, all distract for what sort of child could he beget? What could vice beget? Is not his whole course from the ghost to restore goodness and not vice to the marriage beds of Denmark? "Why wouldst thou be a breeder of sinners? I could myself accuse me of more things that it were better my mother had not bourne me." He backs away from her when she would come near, because he feels himself the weight of his "too, too sullied flesh." And finally, realizing that if he goes through with his action, he will lose her and the child too, he warns her, "To a nunnery go, and quickly too. Farewell."

* They do not speak again after that until the Mousetrap. And yet when they do meet there's another dynamic at work. She tries to be the Ice Queen. He tries to be the Rougish Winking Knave. And yet while the play within a play progresses, there are moments of true tenderness, of aching rawness, moments when they almost say, "I'm sorry" - but that time constrains them. "Tis brief, my lord." "As woman's love." "That's a fair thought to lie between a woman's legs." "What is, my lord?" (Embarassment, he's gone too far.) "...Nothing." And then when she's taken off, dragged away by her father, a moment - just a moment - a look - an unspoken exchange - and Hamlet's future happiness slips from him like that.

* The remainder is played out separately. The lovers are not allowed to meet again. Ophelia, realizing as she sees her father's dead body taken out as Hamlet is led away enchained, that her own life is in danger now that there's none in the court to protect her, chooses Hamlet's mode of madness. For who would kill a mad woman who knows nothing, who cannot remember that fateful Moustrap, who certainly did not know what it portended? Everything she says is about her father, no? But when her brother comes she tries - how does she try! - to make him look in her eyes, see the sanity there. But Laertes is caught up with a father's grief, and with Claudius' seeming sweetness, that he does not listen to any reason whatsoever. And so he does not see Gertrude's patient stillness, like a panther before it strikes, or a cobra when it coils, but lets Ophelia be led away by guards whilst he goes to learn how best to damn his own soul.

* How should Horatio break to Hamlet Ophelia's death? He brings him to the graveyard. He bites his tongue when Hamlet whispers to Yorick's skull with a tenderness, a sadness, a bitter hope, "Go. Make her laugh at that." And then the funeral comes, what with one thing and another, Hamlet puzzles together the Gravedigger's riddles and knows what only one other still living knows: that not only Ophelia died, but his unborn child as well.

* And perhaps this small saint in Heaven is the one who finally intercedes for his father, when Hamlet realizes that there is "a certain Providence in the fall of every sparrow...the readiness is all. Let be." Hamlet, with all he loves now either in Heaven or hopefully bound for it, goes to the clumsy trap Claudius and Laertes have set out, ready to die - freed at last to carry out the ghost's revenge at such an opportunity - freed at last to have no fear for his life by surrendering all his life to One far greater than himself. This, then, is our apotheosis. And if the rest is silence, it's only because no ghost need come back to right another wrong. It is done.

Anywho those are my thoughts. Yup yup yup.

Mood: OJ is a balm unto my throat

Music: "Keep Myself Awake" a la the first Buffy album, although I use it on the current Hamlet Inspirational CD.

Thought: Too many to judge by the length of this post!

The sporadic ramblings of Emily C. A. Snyder - devoted to God, theatre, writing, and much randominity.

The sporadic ramblings of Emily C. A. Snyder - devoted to God, theatre, writing, and much randominity.

3 Comments:

Dear lord that made me want to cry but if you really think about it it makes sense

Thank you so much.

Oh goodness I love all of what you have said. Read the book "Ophelia" by Lisa Klein. You would absolutely love it. It shows Ophelia's side of the story and it's amazing. :)

Post a Comment

<< Home