The Deadly Theatre

First, I'm reading The Prestige (my Christmas Eve gift), which is in many ways far different from the movie (surprise surprise) and yet thus far I'm finding both equally satisfying. The Prestige, the novel, is perhaps a bit more Wuthering Heights in terms of its multiple narrators than I had supposed, and more curious in its use of the epistolary form than I had also supposed (I thought it should jump back and forth a bit more, like the movie does or a typical epistolary novel), but regardless I am enjoying it very much thus far. This is a testament to the quality of the literature, since the plot is already "spoiled" for me. Bravo, book!

Second, I'm working on the extras for Hamlet, one of which I have posted on YouTube. I'm not quite sure how or if I can do a blooper reel from the performances, since by and large the actors did a fair job of covering any dropped lines, etc. And it's so awfully difficult to show something that isn't there! (Reminds me of invisible turtles....)

But the real reason for writing is, as the title implies, Thoughts on the Deadly Theatre. Scattered, randominity thoughts, granted, but scattered for due consideration.

A Definition of Deadly Theatre

Peter Brooke wrote in his The Empty Space about what he called the Deadly Theatre - that is, theatre that follows in the "tradition" of how something has been done before simply for lack of imagination and to cater to the smug comfort of the supposed and self-proclaimed intelligentsia. This is the sort of theatre that, as far as it is able, uses the same exact direction, choreography, stage and costume design and character work as the original production in some sort of thought that this is "faithful and true" without ever thinking that at one time the pale shadow of what he is copying was vital and original.

Theatre is a medium of change. No one performance is the same as the other. And no one audience member's experience of the "same exact play" is unchanging from one performance to the next. The very magic of theatre is this living quality. A performer will emphasize one line one night that he won't the next. He'll make one gesture, turn his eyes upward, give a half-smile in one place on one night that he won't think to do the following night. And the audience member who is enthralled by the newness of the first performance she sees - whether it is the best of that run or the worst - will not be thrilled in the same way when she goes back to see the same actors, same direction, same artistic choices in the same venue the following night because she will know what comes next and invariably compare it to her previous experience. And the time she comes after that will be a different experience altogether than any of the ones that have come before. And this is how it should be.

If, then, theatre is by its very means of existence living and changing (enough to make any Buddha or Einstein roll over in raptures), the Deadly Theatre is that which strives to freeze an audience's impression of a single night's work into a hellish eternity. They mistake the original direction, that night's interpretation, that artist's handicraft as the only possible means of presenting the play well, without ever asking why any of the artists involved made those choices. He does not take into account the thousands preliminary questions that the artists make before, during, and even into performance in order to shape the show specifically for that time and place. He does not ask himself whether the staging or the stage say something ideological - and therefore, further, whether he agrees with that ideology or whether there is a better way to present the same idea - but he looks at it and presumes that the magic is inherent in those bits of timber and not in the ideas that went into choosing that specific type of wood.

Deadly Theatre and Shakespeare

The traditional Deadly Theatre goer wants all Shakespearean work to be done as near as possible to however we think Shakespeare might have put on his plays, but the modern Deadly Theatre goer wants all Shakespeare to be like whatever version he saw that he liked best. However, most Deadly Theatre patrons seem to want Shakespeare to die as well. Or, if needs must, he should be so lampooned and twisted and teenyboppered that he's barely recognizable. Since, however, there can be no discourse about the Deadly Theatre goer who hates Shakespeare, let's take a look at the Deadly Theatre goer who wants to stagnate the Bard.

This fellow, at least in our modern day, seems to have a few criteria that differ from Peter Brooke's time. Since he has been, whether wittingly or no, influenced by Brooke's own iconoclast productions and the general tenor of revolution in the 60's, the modern Deadly Theatre goer (who does not reject Shakespeare) expects a few things from his Deadly Shakespeare. In no particular order they appear to be:

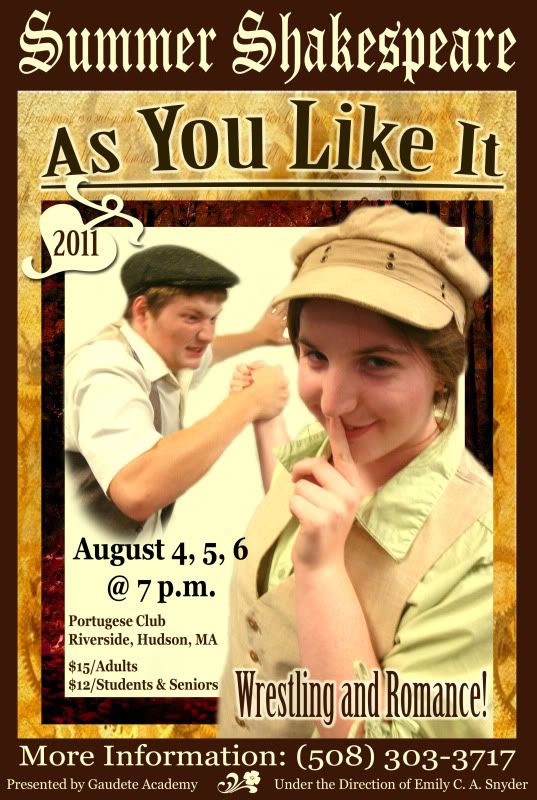

1) That the presentation of the play be done in a non-Shakespearean setting. It doesn't really matter what century the play is put in, so long as there are no tights or doublets to be found. The only exception is for really old companies, or companies with claims to old ties (see the Globe). And, for some reason, the comedies. The comedies can be olde - mostly because no one seems to understand them.

2) However, while Shakespeare ought to be done in any time period but his own, the interpretation of the piece must align perfectly with whatever the public school textbooks are currently propagating. Hence, Romeo and Juliet is the greatest love tragedy ever, Hamlet is about a crazy guy, Midsummer's is a bit of fluff, Macbeth should never be said, and Julius Caesar is mostly about lending ears. Oh, and Taming of the Shrew should have a feminist or chauvinist swing - take your pick. Freudian, and most recently, homoerotic subtext should abound; every single crass joke Shakespeare cracks should be played up, since those are the only ones that the directors frequently get - and if there aren't enough to the director's satisfaction, he should make a few; and if women are playing men they may also be playing androgeny.

3) Regarding the text itself, poor Shakespeare is caught between the continuing cringing idolization of Ye Olde Merrie Serfdirektor and his Jeckyll-like iconoclastic alter-ego. Hence, text tends to be either:

a) Cut up however everyone else has done. This is the most common, since both the amateur and the specialist might make the same cuts, but for different reasons. The amateur will make the cuts because he is relying on a previous performance text that seemed to work. The specialist might make the same cuts because they make the most sense. (Hence poor Fortinbras continually ending up on the cutting room floor. Or the lamentation scene after Juliet's supposed suicide. Or the first scene in Shrew.)

b) Not cut at all and therefore almost invariably interminable. Now, granted there are reasons to every once in a while take out one of the reeeeeeally long or perpetually cut Shakespeares and brush it off and see what it's like with no tampering whatsoever, but usually what one finds is that there's a reason why everyone makes such and such an adjustment - if not for the good of the story, then for the sake of the audiences' bums. However, there's always some folk from the Deadly Theatre who say that if a single line of Shakespeare is touched, it's sacrilege. These are, by and large, the same folk who are absurd about musical theatre, as well. More on this later!

c) Bizarrely edited to seem relevent or to meet time constraints. The best example of this I can give is the Ethan Hawke Hamlet which was so chopped up that it left out anything resembling mirth which meant two hours of sheer depression and greasy hair. Although, come to think of it, the Hallmark Hamlet also did some just strange cuts, as did the recent Twelfth Night with Helena Bonham Carter. In each of these, the thing that seems to go first is the levity. Which, in the case of the latter, is simply ridiculous. Baz Luhrman nearly escaped this trap, until the very end of Romeo+Juliet when he pulled a near-Sheridan on the ending and left out quite a bit in the graveyard scene. (Booooooo.) These folk, while commendably attempting to think outside the box, are not always able to justify their cuts and seem to make the cuts initially out of an homage to Brookian ideals. Brooke himeslf would have something to say about that!

Musicals and the Deadly Theatre

I've run into the slavish traditionalist more in musical theatre than in straight plays (perhaps mostly because I've done fewer straight plays in my time), and do wonder whether the Deadly Musical Theatre goer isn't more numerous and therefore more mob-ly vindictive than the mere Deadly Straight Theatre goer. Across the country, in every high school and every high school summer program and every community theatre that is essentially high school theatre with the matriculated, we find examples of the Deadly Musical Theatre.

This is the sort that - since we often do know what the original staging was - demand nothing but the original staging. (Unless it's staged by a Brit. The English, having far cooler accents than ourselves and being capable of understanding more than just the naughty bits of Shakespeare are allowed to do whatever they like to anything. Oh, and Hollywood. But that's because people in Hollywood don't know what they're doing.) Any change to the original blocking is cause for an auto de fe, not seen since Voltaire's imagination ran wild. The suggestion that, horrors, there might be more than one means to staging a musical or more than one interpretation of a character is nothing less than blasphemy. Original thought is wildly discouraged in the musical world...and this is very deadly.

Those who first stage musicals are doing the best they can with the materials they have at the moment. They're working without the benefit of hindsight, they're working within the tradition they have at the moment, and with the actors and innovations which are available to them - nothing more. They're guessing the first time round, just like every act of theatre guesses, that this might work and this might not. They're saying, for example, "Well, Cole Porter's a bright chap, and these folks paid to be here, let's give them TWELVE VERSES of the same tune! Write some more Cole! We won't edit!" When, in fact, Mr. Porter, his play, and the audience would be better served with some well-chosen verses. Or, heck, with verses that actually moved the plot along.

This same difficulty can be found in ballets and operas. Both of these are notorious for not only repeating the same staging, but even the same costumes, sets, lighting designs, orchestra members, and stage doormen. Occasionally an innovator comes along who seems more set on simply mucking things up a bit - a Baz or a Brooke or that fellow who did the homoerotic Swan Lake - and they're hailed (sometimes rightly, sometimes out of sheer bored desperation) much like fellows who put on funny noses and tell bizarre jokes at an endless cocktail party are hailed. But, by and large, the opera and ballet world seem to trudge inevitably back to the quagmire of their past. (I understand there's some innovation going on in both worlds, but being only on the fringes, I can't speak to it myself.)

None of this need be so. Were artists and audience alike to look at a work and whether or not the execution of that work was successful - whether it made a unified whole - whether it spoke to something relevant and true - then perhaps we could get on with the business of creating theatre. But since the Deadly Theatre hangs on so in the public mind, and perpetuates itself generation upon adolescent generation, it seems that the process of bringing good art - not just to an audience, but to future artists - is simply an equally infinite process.

Pragmatism and the Deadly Theatre

What is suggested - that staging ought to be based on whether it works and not on whether it's traditional - appears to be a sort of pragmatism. But it is not. Pragmatism is fundamentally uninterested in whether what works is also what is honest. It's far too Machiavellian at its base - although politely Machiavellian, which is its difficulty.

Rather, we should be interested not only in what works for a show, for a particular audience or a particular artist, but also what is true. The recent Mirimax version of Midsummer Night's Dream *works* but it twists the story so that it is not true. Bottom cannot be the hero. He is an ass. It's an interesting take, but ultimately false. Whereas Branaugh's Love's Labour Lost as the loss of innocence before World War I is both an interesting take and a relevant one. It works in the stage version of West Side Story for the girls' chorus to get one measly number in "America" - but it's more true, as in the filmed version, for the song to be an argument between the Shark men and women.

Nor is there only one truth found in any given play. Romeo and Juliet can play truly both as a tragedy and an absurdity of adolescent love. The version of Hamlet that retains Fortinbras to bring the goings-on of Elsinore into the global arena is as true as the version that is interested solely in the family drama therein. It's equally true to set La Boheme in Paris 1900 and in Paris 1950. Having Lois dance around with a costume rack in "Always True to You" says something true about her character, as does having her dance with her male harem. It all depends on whether the essential choice and reason behind the choice is true, whether it fits with the story as a whole, and whether it is capable of being executed. (For example, if one's stage concept was for Damocles' Sword to be suspended above the actors, one had better be able to make sure that sword wouldn't come down - or drop the concept and find another means!)

And now, mes petites, I've written far too much! In further and non-relevatory news, I went out inbetwixt this post and other goings on to take a walk with Dad, Jules and Pete down on the bike track, and ended up going an extra two miles walking back home with Pete while Jules and Dad drove back...and we beat them on foot by five minutes! HA! Only now my legs feel a little wobbly because we did go pretty fast. And the remainder, I shall remain obscure. Suffice to say, I am very glad for Julie. Mmmmwah.

Mood: Wobbly

Music: "I Walk Alone" mix that Jules found in her great cleaning!

Happy Feast: Of the Innocents! Oh, Holy Martyrs, pray for us!

First, I'm reading The Prestige (my Christmas Eve gift), which is in many ways far different from the movie (surprise surprise) and yet thus far I'm finding both equally satisfying. The Prestige, the novel, is perhaps a bit more Wuthering Heights in terms of its multiple narrators than I had supposed, and more curious in its use of the epistolary form than I had also supposed (I thought it should jump back and forth a bit more, like the movie does or a typical epistolary novel), but regardless I am enjoying it very much thus far. This is a testament to the quality of the literature, since the plot is already "spoiled" for me. Bravo, book!

Second, I'm working on the extras for Hamlet, one of which I have posted on YouTube. I'm not quite sure how or if I can do a blooper reel from the performances, since by and large the actors did a fair job of covering any dropped lines, etc. And it's so awfully difficult to show something that isn't there! (Reminds me of invisible turtles....)

But the real reason for writing is, as the title implies, Thoughts on the Deadly Theatre. Scattered, randominity thoughts, granted, but scattered for due consideration.

Peter Brooke wrote in his The Empty Space about what he called the Deadly Theatre - that is, theatre that follows in the "tradition" of how something has been done before simply for lack of imagination and to cater to the smug comfort of the supposed and self-proclaimed intelligentsia. This is the sort of theatre that, as far as it is able, uses the same exact direction, choreography, stage and costume design and character work as the original production in some sort of thought that this is "faithful and true" without ever thinking that at one time the pale shadow of what he is copying was vital and original.

Theatre is a medium of change. No one performance is the same as the other. And no one audience member's experience of the "same exact play" is unchanging from one performance to the next. The very magic of theatre is this living quality. A performer will emphasize one line one night that he won't the next. He'll make one gesture, turn his eyes upward, give a half-smile in one place on one night that he won't think to do the following night. And the audience member who is enthralled by the newness of the first performance she sees - whether it is the best of that run or the worst - will not be thrilled in the same way when she goes back to see the same actors, same direction, same artistic choices in the same venue the following night because she will know what comes next and invariably compare it to her previous experience. And the time she comes after that will be a different experience altogether than any of the ones that have come before. And this is how it should be.

If, then, theatre is by its very means of existence living and changing (enough to make any Buddha or Einstein roll over in raptures), the Deadly Theatre is that which strives to freeze an audience's impression of a single night's work into a hellish eternity. They mistake the original direction, that night's interpretation, that artist's handicraft as the only possible means of presenting the play well, without ever asking why any of the artists involved made those choices. He does not take into account the thousands preliminary questions that the artists make before, during, and even into performance in order to shape the show specifically for that time and place. He does not ask himself whether the staging or the stage say something ideological - and therefore, further, whether he agrees with that ideology or whether there is a better way to present the same idea - but he looks at it and presumes that the magic is inherent in those bits of timber and not in the ideas that went into choosing that specific type of wood.

The traditional Deadly Theatre goer wants all Shakespearean work to be done as near as possible to however we think Shakespeare might have put on his plays, but the modern Deadly Theatre goer wants all Shakespeare to be like whatever version he saw that he liked best. However, most Deadly Theatre patrons seem to want Shakespeare to die as well. Or, if needs must, he should be so lampooned and twisted and teenyboppered that he's barely recognizable. Since, however, there can be no discourse about the Deadly Theatre goer who hates Shakespeare, let's take a look at the Deadly Theatre goer who wants to stagnate the Bard.

This fellow, at least in our modern day, seems to have a few criteria that differ from Peter Brooke's time. Since he has been, whether wittingly or no, influenced by Brooke's own iconoclast productions and the general tenor of revolution in the 60's, the modern Deadly Theatre goer (who does not reject Shakespeare) expects a few things from his Deadly Shakespeare. In no particular order they appear to be:

1) That the presentation of the play be done in a non-Shakespearean setting. It doesn't really matter what century the play is put in, so long as there are no tights or doublets to be found. The only exception is for really old companies, or companies with claims to old ties (see the Globe). And, for some reason, the comedies. The comedies can be olde - mostly because no one seems to understand them.

2) However, while Shakespeare ought to be done in any time period but his own, the interpretation of the piece must align perfectly with whatever the public school textbooks are currently propagating. Hence, Romeo and Juliet is the greatest love tragedy ever, Hamlet is about a crazy guy, Midsummer's is a bit of fluff, Macbeth should never be said, and Julius Caesar is mostly about lending ears. Oh, and Taming of the Shrew should have a feminist or chauvinist swing - take your pick. Freudian, and most recently, homoerotic subtext should abound; every single crass joke Shakespeare cracks should be played up, since those are the only ones that the directors frequently get - and if there aren't enough to the director's satisfaction, he should make a few; and if women are playing men they may also be playing androgeny.

3) Regarding the text itself, poor Shakespeare is caught between the continuing cringing idolization of Ye Olde Merrie Serfdirektor and his Jeckyll-like iconoclastic alter-ego. Hence, text tends to be either:

a) Cut up however everyone else has done. This is the most common, since both the amateur and the specialist might make the same cuts, but for different reasons. The amateur will make the cuts because he is relying on a previous performance text that seemed to work. The specialist might make the same cuts because they make the most sense. (Hence poor Fortinbras continually ending up on the cutting room floor. Or the lamentation scene after Juliet's supposed suicide. Or the first scene in Shrew.)

b) Not cut at all and therefore almost invariably interminable. Now, granted there are reasons to every once in a while take out one of the reeeeeeally long or perpetually cut Shakespeares and brush it off and see what it's like with no tampering whatsoever, but usually what one finds is that there's a reason why everyone makes such and such an adjustment - if not for the good of the story, then for the sake of the audiences' bums. However, there's always some folk from the Deadly Theatre who say that if a single line of Shakespeare is touched, it's sacrilege. These are, by and large, the same folk who are absurd about musical theatre, as well. More on this later!

c) Bizarrely edited to seem relevent or to meet time constraints. The best example of this I can give is the Ethan Hawke Hamlet which was so chopped up that it left out anything resembling mirth which meant two hours of sheer depression and greasy hair. Although, come to think of it, the Hallmark Hamlet also did some just strange cuts, as did the recent Twelfth Night with Helena Bonham Carter. In each of these, the thing that seems to go first is the levity. Which, in the case of the latter, is simply ridiculous. Baz Luhrman nearly escaped this trap, until the very end of Romeo+Juliet when he pulled a near-Sheridan on the ending and left out quite a bit in the graveyard scene. (Booooooo.) These folk, while commendably attempting to think outside the box, are not always able to justify their cuts and seem to make the cuts initially out of an homage to Brookian ideals. Brooke himeslf would have something to say about that!

I've run into the slavish traditionalist more in musical theatre than in straight plays (perhaps mostly because I've done fewer straight plays in my time), and do wonder whether the Deadly Musical Theatre goer isn't more numerous and therefore more mob-ly vindictive than the mere Deadly Straight Theatre goer. Across the country, in every high school and every high school summer program and every community theatre that is essentially high school theatre with the matriculated, we find examples of the Deadly Musical Theatre.

This is the sort that - since we often do know what the original staging was - demand nothing but the original staging. (Unless it's staged by a Brit. The English, having far cooler accents than ourselves and being capable of understanding more than just the naughty bits of Shakespeare are allowed to do whatever they like to anything. Oh, and Hollywood. But that's because people in Hollywood don't know what they're doing.) Any change to the original blocking is cause for an auto de fe, not seen since Voltaire's imagination ran wild. The suggestion that, horrors, there might be more than one means to staging a musical or more than one interpretation of a character is nothing less than blasphemy. Original thought is wildly discouraged in the musical world...and this is very deadly.

Those who first stage musicals are doing the best they can with the materials they have at the moment. They're working without the benefit of hindsight, they're working within the tradition they have at the moment, and with the actors and innovations which are available to them - nothing more. They're guessing the first time round, just like every act of theatre guesses, that this might work and this might not. They're saying, for example, "Well, Cole Porter's a bright chap, and these folks paid to be here, let's give them TWELVE VERSES of the same tune! Write some more Cole! We won't edit!" When, in fact, Mr. Porter, his play, and the audience would be better served with some well-chosen verses. Or, heck, with verses that actually moved the plot along.

This same difficulty can be found in ballets and operas. Both of these are notorious for not only repeating the same staging, but even the same costumes, sets, lighting designs, orchestra members, and stage doormen. Occasionally an innovator comes along who seems more set on simply mucking things up a bit - a Baz or a Brooke or that fellow who did the homoerotic Swan Lake - and they're hailed (sometimes rightly, sometimes out of sheer bored desperation) much like fellows who put on funny noses and tell bizarre jokes at an endless cocktail party are hailed. But, by and large, the opera and ballet world seem to trudge inevitably back to the quagmire of their past. (I understand there's some innovation going on in both worlds, but being only on the fringes, I can't speak to it myself.)

None of this need be so. Were artists and audience alike to look at a work and whether or not the execution of that work was successful - whether it made a unified whole - whether it spoke to something relevant and true - then perhaps we could get on with the business of creating theatre. But since the Deadly Theatre hangs on so in the public mind, and perpetuates itself generation upon adolescent generation, it seems that the process of bringing good art - not just to an audience, but to future artists - is simply an equally infinite process.

What is suggested - that staging ought to be based on whether it works and not on whether it's traditional - appears to be a sort of pragmatism. But it is not. Pragmatism is fundamentally uninterested in whether what works is also what is honest. It's far too Machiavellian at its base - although politely Machiavellian, which is its difficulty.

Rather, we should be interested not only in what works for a show, for a particular audience or a particular artist, but also what is true. The recent Mirimax version of Midsummer Night's Dream *works* but it twists the story so that it is not true. Bottom cannot be the hero. He is an ass. It's an interesting take, but ultimately false. Whereas Branaugh's Love's Labour Lost as the loss of innocence before World War I is both an interesting take and a relevant one. It works in the stage version of West Side Story for the girls' chorus to get one measly number in "America" - but it's more true, as in the filmed version, for the song to be an argument between the Shark men and women.

Nor is there only one truth found in any given play. Romeo and Juliet can play truly both as a tragedy and an absurdity of adolescent love. The version of Hamlet that retains Fortinbras to bring the goings-on of Elsinore into the global arena is as true as the version that is interested solely in the family drama therein. It's equally true to set La Boheme in Paris 1900 and in Paris 1950. Having Lois dance around with a costume rack in "Always True to You" says something true about her character, as does having her dance with her male harem. It all depends on whether the essential choice and reason behind the choice is true, whether it fits with the story as a whole, and whether it is capable of being executed. (For example, if one's stage concept was for Damocles' Sword to be suspended above the actors, one had better be able to make sure that sword wouldn't come down - or drop the concept and find another means!)

Mood: Wobbly

Music: "I Walk Alone" mix that Jules found in her great cleaning!

Happy Feast: Of the Innocents! Oh, Holy Martyrs, pray for us!

The sporadic ramblings of Emily C. A. Snyder - devoted to God, theatre, writing, and much randominity.

The sporadic ramblings of Emily C. A. Snyder - devoted to God, theatre, writing, and much randominity.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home